To see my writing process for this essay click here. To read my blog posts for this essay click here. To view a pdf of this essay click here.

Battle for Dominance: A Freudian Analysis of Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour”

Although Sigmund Freud’s theories are no longer widely accepted in the psychology world, they are still helpful when analyzing literature. Freud’s theories allow readers or critics to interpret a work in a way that helps them understand the characters, or the author, in a new light. Freud believes that people are “driven by the pleasure principle, where sexual desires and aggressive behavior are controlled by the reality principle, the so-called restrictions we follow to conform to proper behavior” (Pennington and Cordell 3.3). The reality principle represses the pleasurable desires people have.

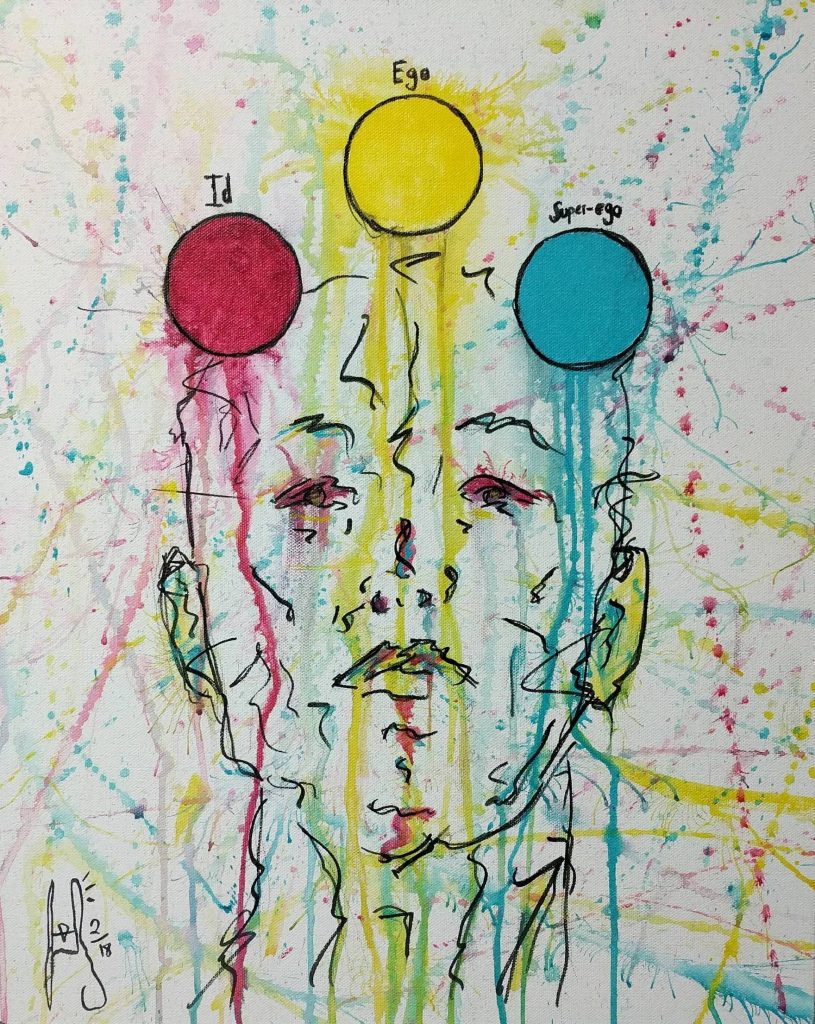

These two ideas, the pleasure and reality principles, are related to another theory of Freud’s: the id, ego, and superego. The id, ego, and superego, as well as the pleasure and reality principles, can be looked at on a spectrum. The id and the pleasure principle are on one end, all aggression and animalistic behavior. The superego and the reality principle are on the other end of the spectrum, morally-driven and societal. The ego rests in the middle of the spectrum, attempting to find a balance between the two. When the ego cannot find that balance, according to Freud, disaster strikes. Freud’s theory of the id, ego, and superego helps to show that Kate Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” is about the internal struggle Louise Mallard faces after learning about the death of her husband; this internal struggle between the id and the superego without the balancing help of the ego is what leads to Louise’s death, a death that ultimately occurs because Louise’s short-lived freedom is ripped away from her.

Louise’s immediate reaction to her husband’s death is one that would be considered socially acceptable. Freud’s theory of the superego can be used to explain this reaction. The superego is “the moral conscience—the ‘law’—that tells us what is right or wrong … and is driven by the reality principle” (Pennington and Cordell 3.3). Additionally, the superego leads us towards actions that are socially acceptable. Louise reacts in a very socially acceptable way when she learns about the death of her husband. She “wept at once, with sudden, wild abandonment” (Chopin 48).

This reaction to such devastating news is not unusual or uncommon, and Freud would argue that at this moment, Louise’s superego is coming to the forefront of her mind and is the one controlling her. The narrator makes note that Louise does not take a moment to let the information about her husband’s death sink in; she immediately starts sobbing, potentially lending to the interpretation that her ego is having a hard time keeping her emotions in check.

When Louise makes her way to her room alone, she sits “with her head thrown back upon the cushion of the chair, quite motionless, except when a sob came up into her throat and shook her, as a child who had cried itself to sleep continues to sob in its dreams” (48). Once again, the act of sobbing when a loved one dies is not the animalistic work of the id, rather the principled work of the superego. Louise should cry after learning about the death of her husband, and she does. What is interesting is the extremeness of her actions, of these sudden sobs that wrack her body, maybe suggesting that she is becoming unhinged or uncontrollable. In any case, the superego is what is guiding Louise’s actions at this point in the story, but the superego soon loses its dominance over her as the internal struggle begins.

Louise’s immediate, socially acceptable reaction quickly turns into something wilder and more animalistic. The id slowly begins to take over Louise’s mind as her ego struggles to find a balance between the id and the superego. The id “is the center of our instinct, our libido, which naturally seeks gratification, and is driven by the pleasure principle” (Pennington and Cordell 3.3). The id is aggressive, biological, and resides in the unconscious, where repressed desires also live. In this particular story, the id can be seen pushing back against the superego when Louise realizes her freedom. She “abandoned herself [and] a little whispered word escaped her slightly parted lips. She said it over and over under her breath: ‘free, free, free!’” (Chopin 49).

Louise has to abandon herself and what she thinks she knows (superego) in order to allow the id to take over. The very act of abandoning herself is the work of the id starting to push the superego out of the way. Repeating the word “free” over and over, each time getting louder with more conviction, is evidence of her id coming to the forefront. The id gradually sneaks up on her until it completely takes over, and Louise’s repressed desire of wanting freedom and independence finally comes to light. She shifts from one end of the spectrum to the other without much intervention from her ego.

As the id continues to overtake her, she begins to wonder how love could have ever overpowered this new impulse she feels. Louise questions what love could “count for in face of this possession of self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being!” (49). The id is all about self-survival, and Louise is feeling this desire on an extreme level. The ego seems rather non-existent, or at most ineffective, at this point, especially when comparing this moment to the image of Louise sobbing in her chair. She goes from missing her husband dearly to wondering how love could have ever compared to the feeling of freedom from him. There is a total shift in her mindset, from superego to id. Freud’s theory suggests that her unconscious desires are now revealed and that Louise has wanted this freedom all along.

Because of the strong battle in Louise’s mind, she barely has time to figure out which voice to listen to and how to mediate between the two of them. Despite the powerful superego and id taking over Louise’s mind, there are some small instances of the ego attempting to find a balance between the two. The ego “is the moderator of the id (pleasure) and the superego (moral conscience). In other words, the ego is the compromise of the id and the superego, a delicate balance of the mind” (Pennington and Cordell 3.3).

Sitting in her room alone, Louise has “a dull stare in her eyes, whose gaze was fixed away off yonder on one of those patches of blue sky. It was not a glance of reflection, but rather indicated a suspension of intelligent thought” (Chopin 48). One could view this as Louise being in shock over the death of her husband, but this image could also be interpreted as Louise’s ego trying to calm her superego and keep her id at bay. The lack of intelligence in Louise’s gaze could signify the fight between the id and the superego going on in her mind, the ego attempting to mediate between the two. She cannot formulate an intelligent thought because of the war raging on in her head.

The next time the ego makes an appearance is when Louise starts to feel the presence of the id. She begins to “recognize this thing that was approaching to possess her, and she was striving to beat it back with her will” (49). Louise can feel the id starting to take over, and her ego works to push it away. Maybe Louise recognizes that the presence coming to possess her will make her feel those repressed feelings, but what is important here is that Louise’s ego fails to keep the id under control.

Freud writes that mental illnesses stem from a faulty ego, an inability to balance the ebb and flow of the superego and id. With the extremity of the reactions Louise has in such a short period of time, the internal fight between the superego and id is what ultimately leads to her death after finding out her husband is actually alive.

The last line of Chopin’s short story is very interesting because of its ambiguity. Accompanied by her sister, Louise walks down the stairs to find that her husband is in fact alive, and she immediately dies. After her death “the doctors came [and] they said she had died of heart disease – of joy that kills” (Chopin 50). Because of the fight for dominance between the id and superego in Louise’s mind, one can look at this ending in two different ways.

Freud writes that the superego “manifests itself essentially as a sense of guilt and moreover develops such extraordinary harshness and severity towards the ego” (30). Louise’s superego could be guilt-tripping her for feeling such joy at the prospect of freedom from her husband, while also telling her to be joyful that he is now alive.

However, the joy mentioned could also be referring to the joy she felt when she thought she was free from her husband. Freud writes that “the ego represents what may be called reason and common sense, in contrast to the id, which contains the passions” (Freud 10). When Louise sees her husband alive, she is reminded of the joy she previously felt and that her passion for freedom is no longer possible, her id winning the fight. Either way, Louise dies of complete shock as her ego is unable to make sense of what is going on and how to react. The ego cannot overpower the passionate id and guilt-ridden superego at the same time.

Chopin’s “The Story of an Hour” is about the internal struggle Louise faces after learning about the death of her husband. Using Freud’s theory, Louise’s ego has a difficult time finding a balance between her id and superego, both of which threaten to completely overtake her. She gets a small taste of freedom and a world where she only has to live for herself before this desire gets ripped away from her when she sees her husband alive.

With Louise’s id pushing against her superego, her ego unable to mediate between the two, the shock is too much for her to handle and she dies. Freud’s theory of the id, superego, and ego, as well as his idea of the pleasure and reality principles, works well with this story to understand Louise and her extreme reactions after her husband’s death. She battles between which actions are socially acceptable and what actions she truly desires.

Ultimately, neither win.

Works Cited

Chopin, Kate. “The Story of an Hour.” Literature A Portable Anthology, edited by Janet E. Gardner, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017, 48-50.

Freud, Sigmund. The Ego and the Id. W.W. Norton, 1962, sigmundfreud.net, www.sigmundfreud.net/the-ego-and-the-id-pdf-ebook.jsp.

Pennington, John, and Ryan Cordell. Writing about Literature through Theory. FlatWorld, 2013.