To see my writing process for this essay click here. To read my blog posts for this essay click here. To view a pdf of this essay click here.

Sensual Virtuosity: Exploring the Homoerotic Nature of Mademoiselle Reisz and Edna Pontellier’s Relationship in The Awakening

Kate Chopin’s The Awakening is a text that has been analyzed under numerous lenses throughout history. Whether critiquing the novel using a feminist, psychoanalytic, or new critical approach, many of these writers view Edna’s story from a heteronormative point of view. As Elizabeth LeBlanc suggests, “The true power of the novel cannot be fully realized unless it is read not only as a feminist text, but as a lesbian text” (LeBlanc 289). A critic should have the understanding that sexual desire is not always heterosexual in nature, and even though Edna Pontellier does not engage in a physical sexual relationship with another woman, she does engage on emotional and psychological levels.

Using the idea of the metaphorical lesbian, as described by Elizabeth LeBlanc, the term “lesbian” can still be applied to Edna. When “lesbian” is applied to Edna, new opportunities arise for interpreting her death and the setting of her death. The woman who perpetuates these desires in Edna and invites her to explore them is Mademoiselle Reisz, whose piano playing ignites a fire within Edna. Mademoiselle Reisz of Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, a figure who represents lesbianism in the nineteenth century, sheds light on the homoerotic desires that are hidden deep within Edna Pontellier, pushing her to break free of the patriarchal and heteronormative society in which she lives. Edna struggles with these newfound feelings she cannot articulate but ends up giving in to the homoerotic desires and committing suicide in the sea, a symbol of homoerotic love.

Mademoiselle Reisz is a woman who continuously fights against the traditional roles of women and embodies numerous lesbian characteristics of the time period. Kathryn Lee Seidel writes that Chopin uses “metaphors of homoeroticism and of witchcraft, the traditional enterprise associated with the female artist, to develop Mademoiselle Reisz’s characterization” (Seidel 199). On the first topic of metaphors of homoeroticism, Mademoiselle Reisz is physically presented with characteristics similar to lesbian stereotypes of the time period. She is described as “disagreeable,” “little,” “awkward,” and with “absolutely no taste in dress” (Chopin 46-47). She is unattractive and disagreeable, traits that coincide with the lesbian figure of the time who was portrayed as “physically deformed, an emblem of her emotional ‘unnaturalness’” (Seidel 200).

Mademoiselle Reisz’s temperament is unlike that of the traditional Victorian woman, clearly. She lives beyond the heteronormative categories and socially accepted definitions of a woman, and because of this, she is portrayed as an “outcast, a grotesque figure who resembles a witch in both her appearance and her ‘unnatural’ desires” (202). Presenting Mademoiselle Reisz as a witch is interesting because it suggests that there is something mystical or dangerous about her as a lesbian.

In another sense, the witch interpretation could be mirroring the social ideals of the time, showing that Mademoiselle Reisz, an artist and a lesbian, is a person who should not be trusted. Mademoiselle Reisz’s homoerotic characteristics do not end at the physical, however. They extend through to her professional and personal life.

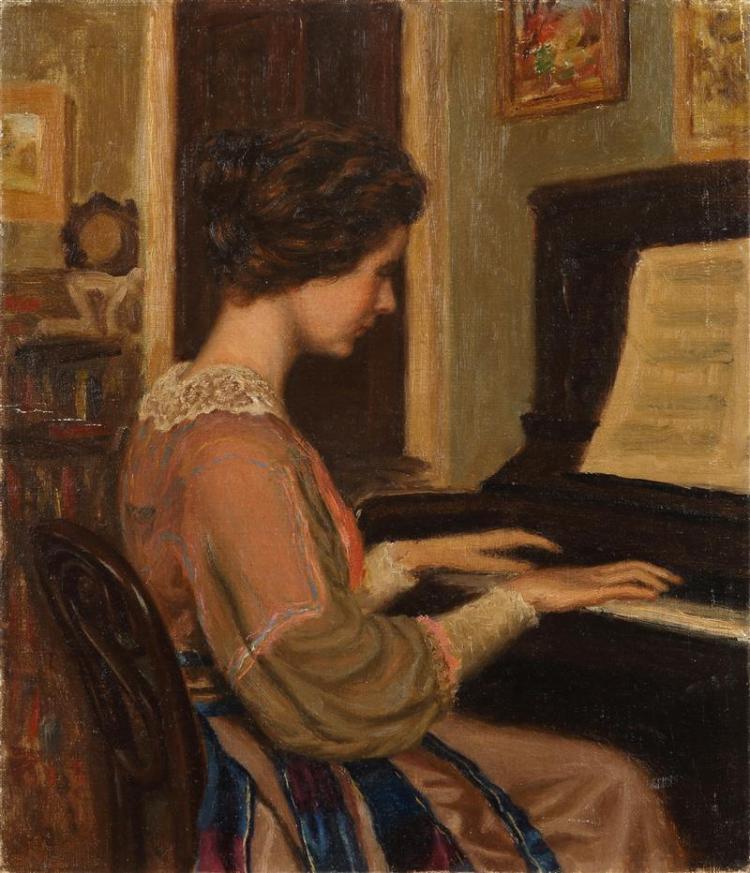

In terms of her profession, Mademoiselle Reisz takes on a traditionally masculine role, blurring gender lines. Any woman who wanted to seriously play the piano outside of the home “was perceived by society as ‘suspiciously masculine,’” making female concert pianists a rarity. (Weber 22). An audience member in The Awakening even remarks that Reisz’s playing “shakes like a man” (Chopin 48). Lesbianism at the time was becoming “increasingly associated with female creativity,” and Mademoiselle Reisz’s musical improvisation abilities can be attributed to that ideal (Seidel 200). She is a woman who refuses to be defined by strict societal rules and ideals and instead embraces the characteristics that make her different.

Another example of Mademoiselle Reisz blurring the gender lines is the separation she makes between herself and other women in society. When Edna visits Reisz for the first time after leaving Grand Isle, Mademoiselle Reisz remarks that she was worried Edna would never visit, that she had just promised to “’as those women in society always do’” (Chopin 85). Mademoiselle Reisz does not include herself in this sentiment, distancing herself from other women in society. She sees herself as someone different, as not categorically or perfectly female.

What Mademoiselle Reisz’s identity means for Edna is that she has someone in her life who is a “non-heterosexual, artist-outsider, who is not bound by sentimental conventions,” someone with “the ability to transport Edna to new levels of reality” (Seidel 203).

The night that Mademoiselle Reisz and Edna meet is the beginning of Edna’s sexual awakening, an awakening that comes directly from Mademoiselle Reisz, rather than from the male characters of the story. The narrator prefaces that this is not the first time Edna has heard an artist at the piano, but that “perhaps it was the first time she was ready, perhaps the first time her being was tempered to take an impress of the abiding truth” (Chopin 47). What is this truth that Edna feels deep within her being? Could it be the admittance of homoerotic desires as she watches Mademoiselle Reisz play the piano? The scene itself is filled with sensual words, as “the very passions themselves were aroused within [Edna’s] soul, swaying it, lashing it, as the waves daily beat upon her splendid body” (47-48).

Of course, at this time, there is no way for Edna to describe the feelings she feels because “the words for the longings of the metaphorical lesbian simply do not exist” (LeBlanc 294). Therefore, Edna is destined to struggle and wrestle with a mysterious truth, something that is unattainable, that she can never quite describe. Edna is drawn to tears by Mademoiselle Reisz’s playing, an example of the powerful feelings that Reisz draws out of Edna, feelings so powerful that they can weaken and break down the foundations of the heteronormative society they live in.

During their time on Grand Isle, Mademoiselle Reisz “seemed to echo the thought which was ever in Edna’s mind; or, better, the feeling which constantly possessed her” (Chopin 68). Once again, there is a vague feeling and thought that Edna experiences, and she only understands it when she is in the company of Mademoiselle Reisz. These feelings of attraction are not one-sided, however. Mademoiselle Reisz raves “much over Edna’s appearance in her bathing suit” (Chopin 71). Chopin shows that women can be attracted to the physicality of another woman and have desires toward them, and even though Edna does not return any physical advances of Reisz, she also does not shy away from them. These experiences on Grand Isle with Mademoiselle Reisz allow Edna to question the heteronormative traditions of society and begin to posit other options.

Mademoiselle Reisz and Edna’s relationship becomes more complex during Edna’s visits to Mademoiselle Reisz’s apartment. Mademoiselle Reisz becomes “the only solace Edna can find” when she is thrust back into her role in society, visiting her “whenever she falls into despondency and hopelessness” (LeBlanc 303). Some of the most sensual parts of the novel come when Mademoiselle Reisz plays the piano for Edna in her home. While Reisz plays the Chopin Impromptu, “Edna was sobbing, just as she had wept one midnight at Grand Isle when strange, new voices awoke in her” (Chopin 87). The comparison to her time at Grand Isle suggests that Edna only allows these feelings to overtake her when she is with Mademoiselle Reisz; she only feels safe enough to let these voices speak while with this other woman.

Edna gets exposed to a different lifestyle when she is with Mademoiselle Reisz, a different way of expressing femininity. During Edna’s second visit to Mademoiselle Reisz’s apartment, a visit that “quieted the turmoil of Edna’s senses,” Mademoiselle Reisz further forces Edna to question her decisions (Chopin 101). This time, the music “penetrated [Edna’s] whole being like an effulgence, warming and brightening the dark places of her soul” (103). This entire scene is sensual, with the language used and the visual imagery of the scene: “two women alone in a room, one playing music which arouses the other” (Seidel 202).

With Mademoiselle Reisz’s piano playing plus her conversation with Edna about men, she forces Edna to question the world in which she lives and the pressures that are constantly on her, pressures that do not seem to riddle Mademoiselle Reisz with the same amount of grief. Ultimately, she is teaching Edna that there are different ways to be a woman, that society does not have to determine how one expresses their femininity. However, Edna must realize that she cannot give in to her homoerotic desires in this lifetime because of those pressures on her, and she ends her life.

Because of her experiences with Mademoiselle Reisz, Edna wishes for a world where she can truly be herself and be free, but she commits suicide when she realizes that will never be possible for her. The sea being the place where Edna ends her life is significant because its “erotic voice… murmurs and whispers to Edna throughout the novel,” much like Mademoiselle Reisz’s music (Weber 20). The sea continuously calls to Edna in a “seductive, never-ceasing” voice, much like a lover, and Edna eventually gives in (Chopin 138). This sea that “swelled lazily in broad billows that melted into one another” is portrayed as a sensual entity in the story, something that Edna goes back to time and time again (49). With this quote, there is an image of two lovers coming together to become one. She meets this lover “naked in the open air” and allows it to enfold her “body in its soft, close embrace” (Chopin 138).

Edna’s return to the sea is more of a sensual act than a childish one. She is not returning to a metaphorical mother-figure or back to the womb; instead, she is reuniting with a lover she can no longer deny. There is strength in this reunion, in refusing to participate in a society that does not accept her. On the other hand, Edna does die; she does not get to live freely in her world.

Perhaps if this story was written in the 21st century she would be able to be free, separate from a male figure without having to die. In the 18th century, however, the idea of a woman being unmarried was preposterous, let alone a woman being attracted to other women. Edna had to die in order to show the danger of a woman like her. These final moments of Edna’s life are not about her escaping reality or falling victim to the heteronormative, patriarchal constructs of society; they are about her refusing to keep fighting against the thoughts in her head and instead giving in to her true feelings.

Throughout The Awakening, Mademoiselle Reisz serves as a symbol of the lesbian artist, working to help Edna realize her homoerotic desires and break free of the constraints society places on women. Edna cannot exist in society because of the pressures that she is unable to get rid of. Even though she wishes to have the carefree nature that Mademoiselle Reisz possesses, she realizes this is not possible for her.

Living in a world where no man can satisfy her and where no woman can make her comfortable enough, Edna turns to the sea, a metaphor for lesbian love. Her death, when viewed through a heterosexual lens, is an attempt at escaping a life she cannot handle. Her death, when viewed through a queer lens, is a surrender to her true feelings, a choice to be free. As Elizabeth LeBlanc writes, readers are “invited into the text, into the water, into the mind of the metaphorical lesbian, as she and her lover enter each other and become one” (LeBlanc 306).

Works Cited

Chopin, Kate. The Awakening. Edited by Nancy A. Walker, 2nd ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000.

LeBlanc, Elizabeth. “The Metaphorical Lesbian: Edna Pontellier in The Awakening.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 15, no. 2, 1996, pp. 289–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/464138.

Seidel, Kathryn Lee. “Art is an unnatural act: Mademoiselle Reisz in ‘The Awakening.’.” The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 2, 1993, p. 199+. Gale Academic Onefile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A14145972/AONE?u=waicu_stnorbert&sid=AONE&xid=46ecde98. Accessed 27 Oct. 2019.

Weber, Susan G., “Undermining Heteronormativity in Kate Chopin’s The Awakening” (2014). \ETD Archive. 847. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/847.